FranceAndUS: Sports and Diplomacy Hiding in Plain Sight

Sport can promote diplomacy, even between kindred democracies.

For more than a century, different types of sports diplomacy have fostered stronger relations between the United States and its oldest ally, France.

Although the cultural endeavors of food, fashion, or film drive public consciousness of citizen interactions, the French and American sports story hides in plain sight. Today sports serve as one of the more democratic milieus in both societies, thus sports diplomacy between these two countries is an instructive example of how this prism exhibits the intersection of sport and democracy.

Read more via “FranceAndUS: Sports and Diplomacy Hiding in Plain Sight” by Carole Ponchon and Lindsay Krasnoff in SportandDev.org

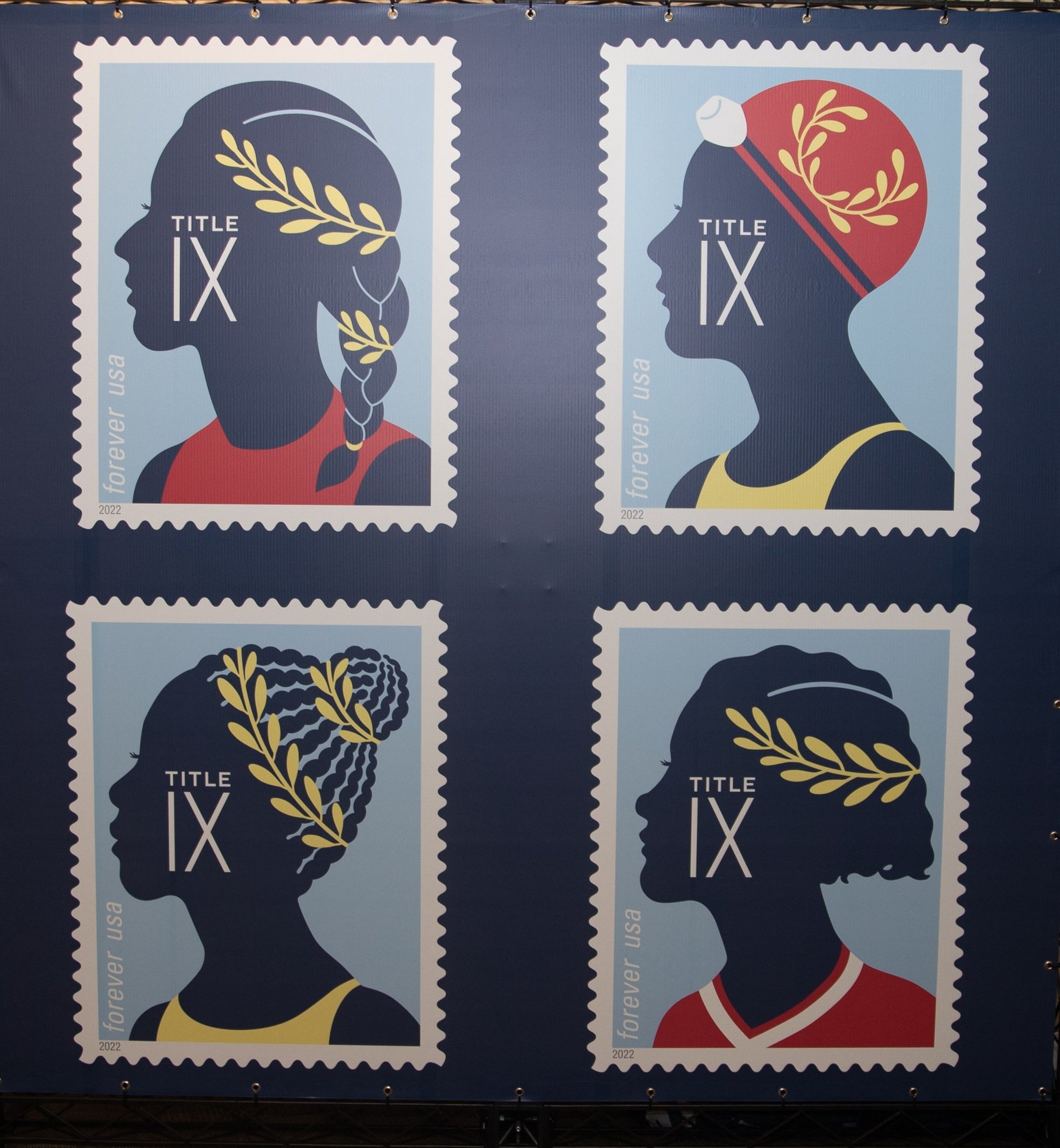

Title IX at 50: Beyond the United States

Today’s celebration of Title IX’s 50th anniversary focuses on how this legislation has benefitted generations around the United States–but it’s also had an impact on France, too.

Today’s celebration of Title IX’s 50th anniversary focuses on how this legislation has benefitted generations around the United States–but it’s also had an impact on France, too.

Title IX of the 1972 Education Act stipulates that “no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Those 37 words have had multidimensional impacts, including providing greater opportunities for women to pursue education while playing sports. Not just American women, but French women, too.

Many of the Voices in the growing FranceAndUS archive were able to pursue their sports passions thanks to Title IX’s educational and sports benefits, which enabled them to be student-athletes in U.S. schools while pursuing academic studies. And some of them were inspired by or received recognition from legendary U.S. coaches, like University of Tennessee basketball’s Pat Summitt.

“American college really reinforced my technically, basketball, and vision of the game.”

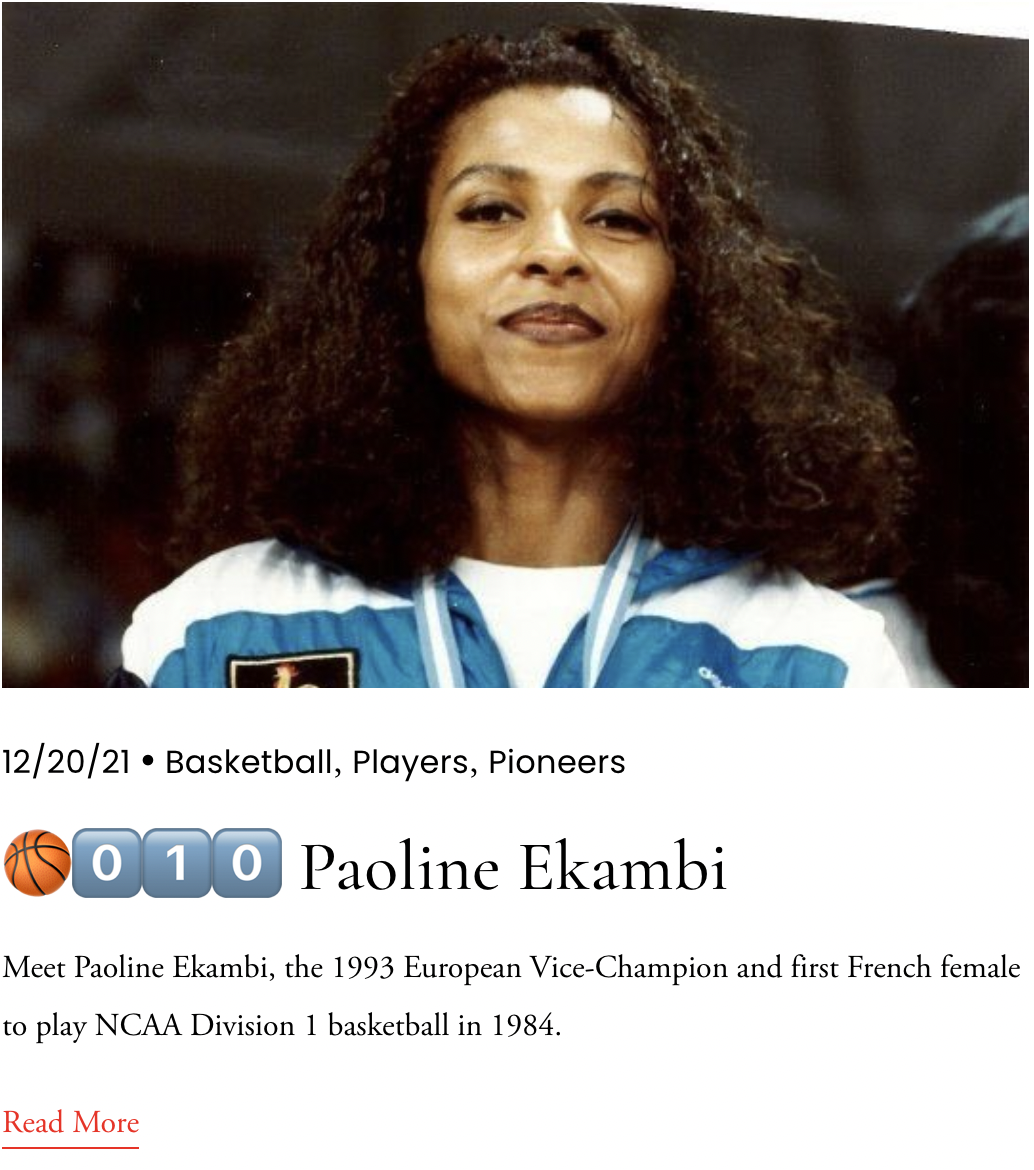

For example, the first French woman to play Division 1 basketball, Paoline Ekambi, in 1984 did so through a bourse at Marist College in Poughkeepsie, New York. As she noted, her motivation to excel at Marist, where she was part of the Big Five, was her desire to demonstrate that French women knew basketball and could play it well. Ekambi attributed her two seasons with the Red Foxes with helping her to become a better player, teammate, and on-court leader. These attributes she passed along to her younger Les Bleues teammates, some of whom had their own American dreams.

Some of this first wave included Katia Foucade-Hoard, the three-time University of Washington Huskies co-captain whose standout career (1991-95) remains inscribed in the school’s record book.

“The thing I learned in the States is that anyone is as good as anyone else, even if on paper it shows that the other team is better. It doesn’t matter when the ball goes up in the air. It’s only at the end of the game that we’ll see who’s the best.”

Foucade-Hoard’s U.S. experience helped inform her service with the national team. At the June 1993 EuroBasket tournament, France fought their way to a silver medal, its first podium finish since 1970. Ekambi was part of that team, as was Yannick Souvré, who played at Fresno State for the 1989-90 season.

Also on that team? Isabelle Fijalkowski, who spun her 1994-95 season with the University of Colorado Buffalos–one of the program’s best–into a springboard to the WNBA in 1997. At the March 1995 NCAA women’s basketball tournament, the team marched through the brackets but fell to Georgia, 79-82, in the Elite Eight, despite Fijalkowski’s valiant efforts (35 points, 9 rebounds, 4 assists).

It’s important to note in this story the two-way knowledge, technical, and cultural exchange facilitated by this Title IX sports diplomacy. As Fijalkowski pointed out, her previous experience in France helped her Colorado teammates.

“They saw that I could help them as a team because there weren’t any other players with my profile…Thus they were delighted.” Isabelle Fijalkowski.

The basketball story has many subsequent generational iterations, including Diandra Tchatchoung (University of Maryland) and Gabby Williams (University of Connecticut) whose transatlantic experiences have helped inform Les Bleues’ successes of the 2010s. And helped fuel the overall growing yet friendly France-USA basketball rivalry.

But it isn’t just at the D1 or national team levels that these Title IX sports diplomacy exchanges are ongoing; it’s there for French women playing D2 and D3 basketball, as well as for U.S. women who compete in the Ligue Féminine de Basketball (LFB), like Penn State alumna Nikki Greene (Angers) and UT alumna and WNBA’s Cassidie Burdick (ASVEL).

There’s a growing intergenerational story of Title IX-inflected FranceAndUS sports diplomacy in soccer. When Title IX was passed in 1972, women’s soccer in France was in the midst of a slow-simmering revival; although one of the early foundational nations in the discipline–the French and English national team captains’ friendly cheek kiss at a 1920 match was the soccer world’s first viral moment–the game fell out of favor and was eventually banned under the Vichy regime. In the 1960s, there was a slow return of organized women’s clubs, and in 1970, the French Football Federation (FFF) recognized the women’s game. But those who played were long marked with numerous stereotypes, which even the current generation active on pitches still fight.

“What I learned in the U.S. and my career in Boston was the team-building effect, how you play not just for yourself but how you’re part of a team with a spirit.”

That’s why it wasn’t until the early 2000s that the first French women came to the United States to play NCAA soccer. FFF Secretary-General Laura Georges was one of the first when she began a Hall of Fame career at Boston College in 2004.

Of note, since Olympique Lyonnais president Jean-Michel Aulas launched and invested in a women’s team in 2004, the team’s rise and decade-long dominance of French and European competition has provided avenues for U.S. players, products of Title IX’s provisions for middle school, high school, and collegiate sports opportunities, to play professionally in France. OL alumna include Alex Morgan, Hope Solo, and Megan Rapinoe, while current squad member Catarina Macario had a standout career at Stanford University before journeying across the Atlantic Ocean.

There are similar intergenerational FranceAndUS stories for other disciplines, such as alpine skiing. Take the Voice of U.S. National Ski Hall of Famer Donna Weinbrecht, the 1992 Olympic gold medalist who was one of the first generations to come of age under the new law. In 1981, she founded her high school’s first ski team, which enabled her to begin training more earnestly and laid the groundwork for her eventual Olympic and World Cup successes.

These storylines are just the start, and more will be added to and highlighted by the archives in the years ahead.

Sport Diplomacy: So what is it?

Sport Diplomacy is how we explain the intersection of the diplomatic realm with the sporting one and the subsequent formation of evolving networks

Contributed By Dr. J. Simon Rofe.

Definition: Sport Diplomacy is how we explain the intersection of the diplomatic realm with the sporting one and the subsequent formation of evolving networks.

It offers, under the premise of the three core characteristics of diplomacy: representation, negotiation, and communication, a conceptual understanding of sport that 1) provides the navigation skills for practitioners to connect with and learn from different parts of the sport diplomacy ecosystem; and 2) helps provide critical reflection for policy makers and practitioners, and scholars, to enhance their practice in these overlapping and conjoined spaces. (Rofe, 2019)

Nelson Mandela said in 2000, “Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire. It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does.” Anyone who has shared in sport’s capacity to heighten emotions with the scoring of a goal, the winning of a race or the triumph over an opponent will recognize the “power” that Mandela acknowledged. In essence Sport has an ability to communicate with vast number and variety of people–and hence facilitate diplomacy.

Why does Sport Diplomacy matter? Sport Diplomacy, or the sport diplomatique, explains the coming together of Representation, Communication and Negotiation–facets of Global Diplomacy–played out through sport as a feature of contemporary society of the past one hundred and fifty years that touches vast numbers of the world’s population either through participation or spectatorship.

Sport has the power to shape the world through diplomatic transactions between not only nation states, but a raft of other actors on a global stage including international sporting bodies such as the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) Special Olympics (SO); non-governmental organisations such as International Sporting Federations; media partners with national, regional and global interests; athletes themselves as potential sporting ‘diplomats’; and business interests that make any Sporting-Mega Event a multi-million pound enterprise. All of this is observed, dissected and recycled by a phalanx of commentators facilitated by twenty first century social media for a global audience. Sport replicates and exemplifies the prevalence of non-state actors and people-to-people [exchanges], which means in this latest iteration of ‘new diplomacy’, private citizens like athletes to play informal diplomatic roles.

The messages that sport carries are rarely singular; and that it can speak to so many different audiences is why it requires the careful decoding and analysis that we can provide.

Dr. J. Simon Rofe is the Global Diplomacy Programme Director and Reader in Diplomatic and International Studies at the Centre for International Studies and Diplomacy, SOAS University of London. Co-Director of the Basketball Diplomacy in Africa Oral History Project, Dr. Rofe’s work has helped build out the sports diplomacy field, both its theory and practice.