Title IX at 50: Beyond the United States

Today’s celebration of Title IX’s 50th anniversary focuses on how this legislation has benefitted generations around the United States–but it’s also had an impact on France, too.

Title IX of the 1972 Education Act stipulates that “no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Those 37 words have had multidimensional impacts, including providing greater opportunities for women to pursue education while playing sports. Not just American women, but French women, too.

Many of the Voices in the growing FranceAndUS archive were able to pursue their sports passions thanks to Title IX’s educational and sports benefits, which enabled them to be student-athletes in U.S. schools while pursuing academic studies. And some of them were inspired by or received recognition from legendary U.S. coaches, like University of Tennessee basketball’s Pat Summitt.

“American college really reinforced my technically, basketball, and vision of the game.”

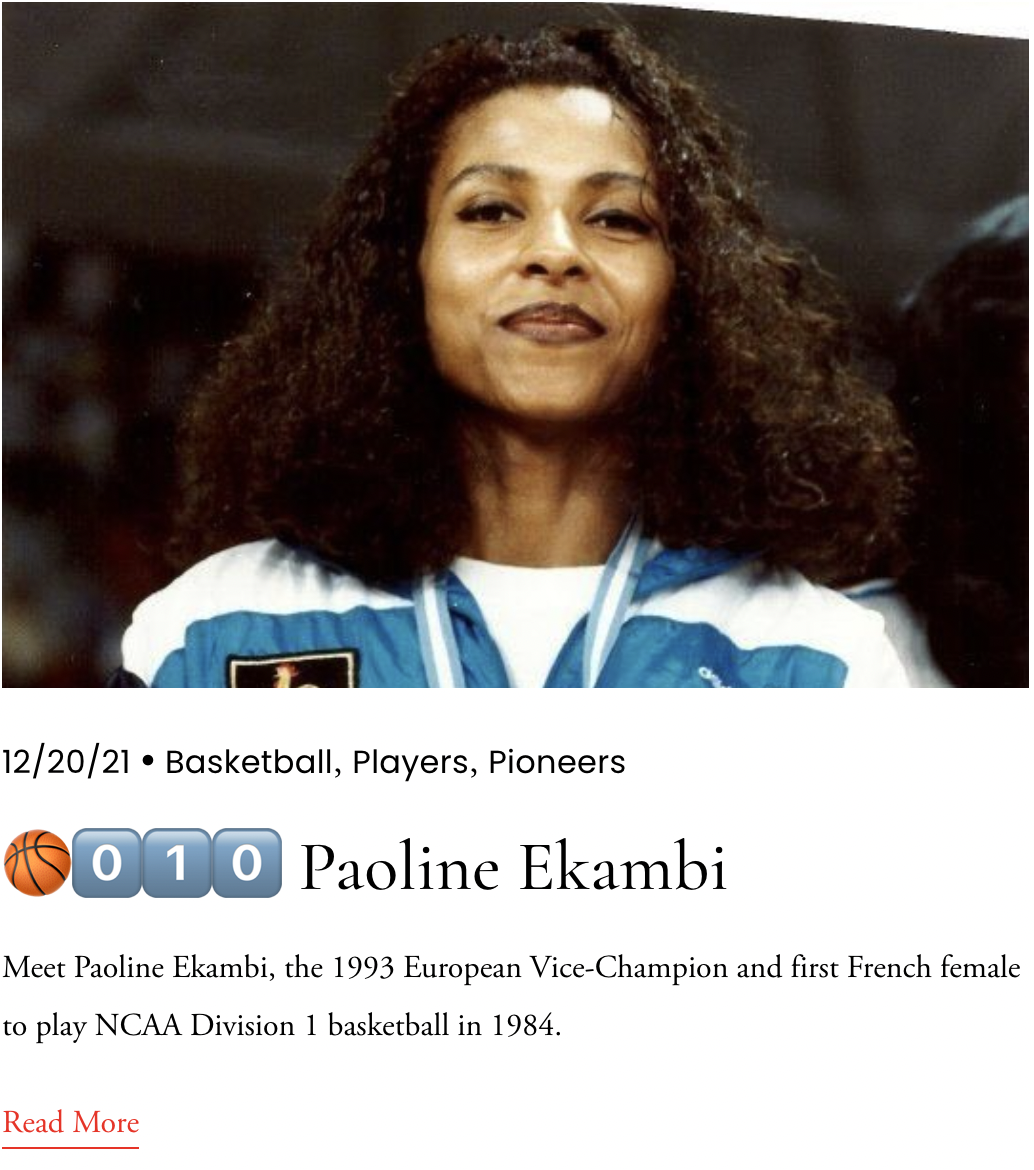

For example, the first French woman to play Division 1 basketball, Paoline Ekambi, in 1984 did so through a bourse at Marist College in Poughkeepsie, New York. As she noted, her motivation to excel at Marist, where she was part of the Big Five, was her desire to demonstrate that French women knew basketball and could play it well. Ekambi attributed her two seasons with the Red Foxes with helping her to become a better player, teammate, and on-court leader. These attributes she passed along to her younger Les Bleues teammates, some of whom had their own American dreams.

Some of this first wave included Katia Foucade-Hoard, the three-time University of Washington Huskies co-captain whose standout career (1991-95) remains inscribed in the school’s record book.

“The thing I learned in the States is that anyone is as good as anyone else, even if on paper it shows that the other team is better. It doesn’t matter when the ball goes up in the air. It’s only at the end of the game that we’ll see who’s the best.”

Foucade-Hoard’s U.S. experience helped inform her service with the national team. At the June 1993 EuroBasket tournament, France fought their way to a silver medal, its first podium finish since 1970. Ekambi was part of that team, as was Yannick Souvré, who played at Fresno State for the 1989-90 season.

Also on that team? Isabelle Fijalkowski, who spun her 1994-95 season with the University of Colorado Buffalos–one of the program’s best–into a springboard to the WNBA in 1997. At the March 1995 NCAA women’s basketball tournament, the team marched through the brackets but fell to Georgia, 79-82, in the Elite Eight, despite Fijalkowski’s valiant efforts (35 points, 9 rebounds, 4 assists).

It’s important to note in this story the two-way knowledge, technical, and cultural exchange facilitated by this Title IX sports diplomacy. As Fijalkowski pointed out, her previous experience in France helped her Colorado teammates.

“They saw that I could help them as a team because there weren’t any other players with my profile…Thus they were delighted.” Isabelle Fijalkowski.

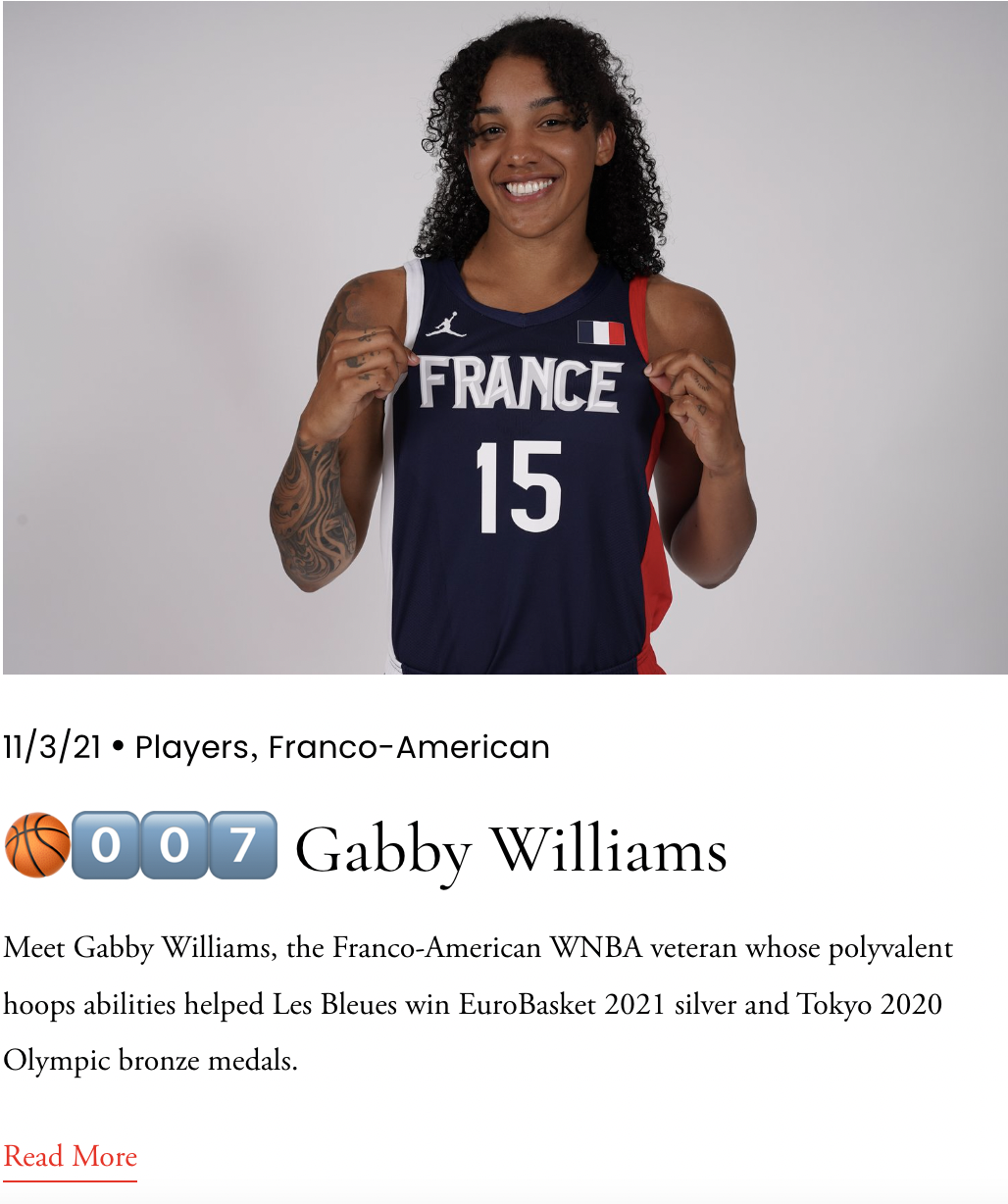

The basketball story has many subsequent generational iterations, including Diandra Tchatchoung (University of Maryland) and Gabby Williams (University of Connecticut) whose transatlantic experiences have helped inform Les Bleues’ successes of the 2010s. And helped fuel the overall growing yet friendly France-USA basketball rivalry.

But it isn’t just at the D1 or national team levels that these Title IX sports diplomacy exchanges are ongoing; it’s there for French women playing D2 and D3 basketball, as well as for U.S. women who compete in the Ligue Féminine de Basketball (LFB), like Penn State alumna Nikki Greene (Angers) and UT alumna and WNBA’s Cassidie Burdick (ASVEL).

There’s a growing intergenerational story of Title IX-inflected FranceAndUS sports diplomacy in soccer. When Title IX was passed in 1972, women’s soccer in France was in the midst of a slow-simmering revival; although one of the early foundational nations in the discipline–the French and English national team captains’ friendly cheek kiss at a 1920 match was the soccer world’s first viral moment–the game fell out of favor and was eventually banned under the Vichy regime. In the 1960s, there was a slow return of organized women’s clubs, and in 1970, the French Football Federation (FFF) recognized the women’s game. But those who played were long marked with numerous stereotypes, which even the current generation active on pitches still fight.

“What I learned in the U.S. and my career in Boston was the team-building effect, how you play not just for yourself but how you’re part of a team with a spirit.”

That’s why it wasn’t until the early 2000s that the first French women came to the United States to play NCAA soccer. FFF Secretary-General Laura Georges was one of the first when she began a Hall of Fame career at Boston College in 2004.

Of note, since Olympique Lyonnais president Jean-Michel Aulas launched and invested in a women’s team in 2004, the team’s rise and decade-long dominance of French and European competition has provided avenues for U.S. players, products of Title IX’s provisions for middle school, high school, and collegiate sports opportunities, to play professionally in France. OL alumna include Alex Morgan, Hope Solo, and Megan Rapinoe, while current squad member Catarina Macario had a standout career at Stanford University before journeying across the Atlantic Ocean.

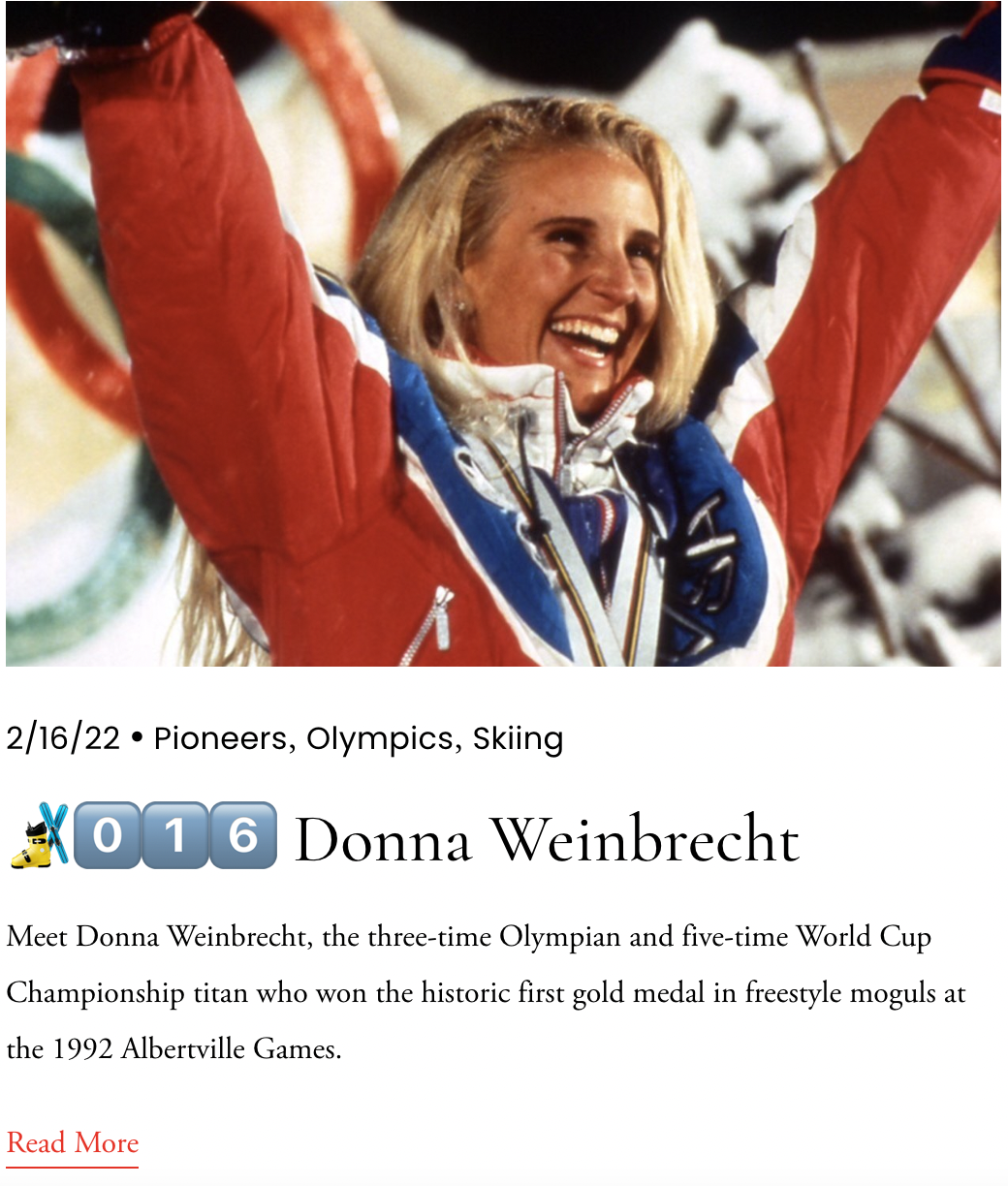

There are similar intergenerational FranceAndUS stories for other disciplines, such as alpine skiing. Take the Voice of U.S. National Ski Hall of Famer Donna Weinbrecht, the 1992 Olympic gold medalist who was one of the first generations to come of age under the new law. In 1981, she founded her high school’s first ski team, which enabled her to begin training more earnestly and laid the groundwork for her eventual Olympic and World Cup successes.

These storylines are just the start, and more will be added to and highlighted by the archives in the years ahead.