🥇🥈🥉0️⃣1️⃣3️⃣ Pierre de Coubertin

Meet Pierre de Coubertin, the French aristocrat who founded the modern Olympic movement and was influenced in part by the sports culture he observed during his 1889 and 1893 trips to the United States.

Born January 1, 1863, in Paris, de Coubertin was fascinated by the 1874 German excavation of Olympia, including the way that civilization used sports and its rituals. Growing up alongside the nascent Third Republic, which used a variety of tools to “create Frenchmen” throughout the realm, de Coubertin was committed to the national cause. As a young man he sought to help reform the republic’s education system; the Ferry Laws created free, secular, compulsory primary education in the 1880s. While mandatory physical education was part of the new system, de Coubertin instead thought that sports—rather than calisthenics and gymnastics—were more ideally suited for building future French citizens, ideas that later influenced his attitudes towards Olympism and the modern Olympic Games.

The Context

De Coubertin was heavily influenced by his studies of English school sports. The efforts of former Rugby School headmaster Thomas Arnold, who implemented field sports such as rugby football to build character and exercise boys’ bodies in the 1840s, left a lasting imprint on the young Frenchman.

Although criticized for his anglophilia, de Coubertin’s views about school sports were also informed by two trips he took to the United States in 1889 and 1893 [1]. During these trips, he studied the ways that sports were used at various U.S. colleges and universities, as well as high schools, and spent much time at Princeton University with history professor William Sloane—who also directed the school’s athletics committee.

Such observations left an imprint. De Coubertin tried, unsuccessfully, to rally support for the Olympic Movement during his 1893 U.S. trip despite assistance from Sloane [2]. Undeterred, the following year he addressed the first-ever Olympic Congress held at the Sorbonne in Paris, the seeds of the modern Games’ rebirth.

The Sports Diplomacy Connection

There are numerous ways that the Olympic Movement and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) engaged in sports diplomacy, but de Coubertin himself served as an informal sports diplomat in his communication, representation, and negotiation vis-a-vis U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt to lobby for his support of the Olympic Games.

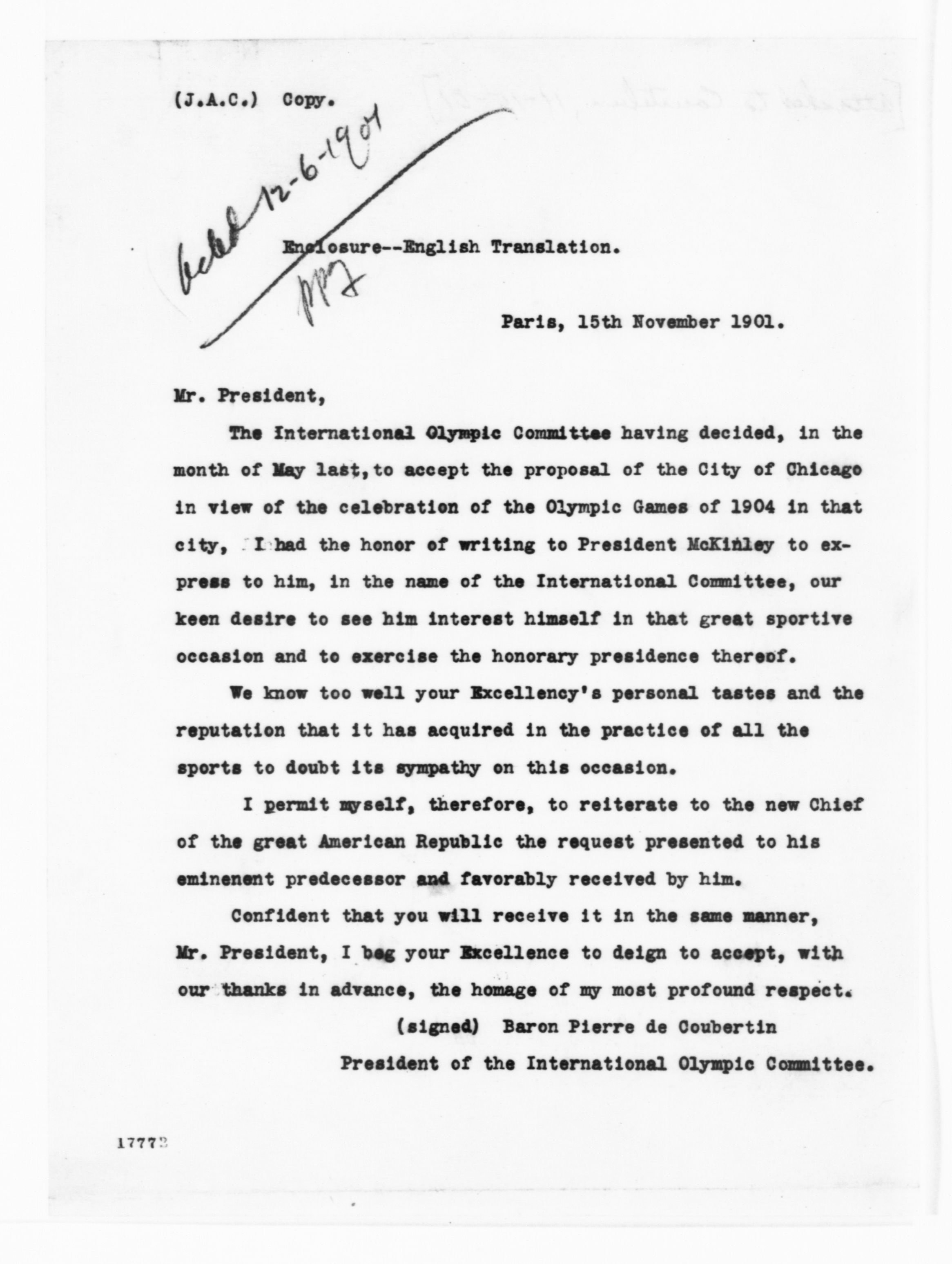

In November 1901, the Frenchman asked the U.S. President to serve as honorary president of the 1904 Chicago Olympic Games.

“We know too well your Excellency’s personal tastes and the reputation that it has acquired in the practice of all sports,” de Coubertin wrote on behalf of the IOC. Roosevelt was a well-known sportsman with a celebrated Tennis Cabinet of advisors and close friends (including after 1902 French Ambassador to the United States J.J. Jusserand)

“It is a matter of very real regret to me that I do not feel at liberty to accept your very kind [offer to] become Honorary President at the Chicago Olympian Games” Roosevelt wrote.

“Unfortunately, after consultation with members of the Cabinet, I feel that it would not do for me to give the unavoidable impression of governmental connection with the games…I have followed with keen interest all that you have done for the promotion of amateur sport and have the most sympathy with your aims; and I congratulate you upon your success in the post, and shall do all I can to make you equally successful in your present undertaking.”

Despite the lack of synergy on this initial request, the two sportsmen struck up a correspondence. Roosevelt later shared with de Coubertin why he boxed far less once in the White House than he would have preferred (so as to not turn up with boxing-related bruises or injuries), as well as the athletic feats of his sons.

[1] Stephan Wassong, “Pierre de Coubertin’s American Studies and Their Importance for the Analysis of His Early Educational Campaign,” (Ergon Verlag, 2002). Via the LA84 Foundation.

[2] Ibid.

Mapping the Connection

From Paris, France to Princeton, New Jersey

Further Reading

[E] Stephan Wassong, “Pierre de Coubertin’s American Studies and Their Importance for the Analysis of His Early Educational Campaign,” (Ergon Verlag, 2002). Via the LA84 Foundation.

[E] Letter from Pierre de Coubertin to Theodore Roosevelt. Theodore Roosevelt Papers. Library of Congress Manuscript Division. https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o36343. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

[E] Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Pierre de Coubertin. Theodore Roosevelt Papers. Library of Congress Manuscript Division. https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o180765. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

[E] George Hirthler, “Celebrating Pierre de Coubertin: The French Genius of Sport Who Founded the Modern Olympic Games,” September 2, 2019, International Olympic Committee.

How to Cite This Entry

Krasnoff, Lindsay Sarah. “Voices: Pierre de Coubertin,” FranceAndUS, https://www.franceussports.com/voices/013-pierre-de-coubertin. (date of consultation).