🎽0️⃣1️⃣2️⃣ DeHart Hubbard

Contributed by Dr. François Doppler-Speranza

DeHart Hubbard via the University of Michigan

Meet DeHart Hubbard, the first U.S. Black athlete to win a gold medal in an individual event at the 1924 Paris Olympics.

DeHart Hubbard was a long jumper, the son of a steel mill worker from Cincinnati, Ohio. Born in 1903, he first attended the segregated Douglass Elementary School and then the predominantly white Walnut Hills High School. A proud Cincinnatian, he made a name for himself in football and track at the amateur level. His detection and recruitment by the University of Michigan demonstrated the extent to which Black athletes were used as bargaining chips by northern universities, which sought to avoid state intervention over racial equality to pursue a structural marginalization of Black athletes. Hubbard qualified for the 1924 Olympics alongside Ned Gourdin, Earl Johnson, and Charley West, and became the first Black athlete to win an Olympic gold medal in an individual event.

The 1924 Olympics reignited anti-American sentiment among the French, but also served as a backdrop for promoting the image of the United States abroad. The latter was a lost cause, according to poet Langston Hughes, who declared,

“But for France! Kid, stay in Harlem! Do they like Americans of any color? No, they don’t.”

Hemingway called Paris a city of sports; by challenging the social and cultural norms of the time, Hubbard also made it a place where American national identity was forged.

Hubbard broke many records at Michigan, sometimes at the expense of his own health. His victory in Paris changed the course of his career, because “we were still in the position of paying a lot of attention to any unusual achievement by a negro,” he later said. Through his fame, he became a mentor to the Black community in Cincinnati, while rewarding the man who helped him get a scholarship and the coach who accepted him into the Michigan athletic program. Hubbard never forgot that it all started in “Cincy.”

The Context

In the 1920s, Black American athletes started to dominate track and field. In an era marked by the promotion of racial uplift and the New Negro, they received widespread publicity through the large-circulation press of the manufacturing belt – The Afro-American, The Chicago Defender, The Norfolk Journal and Guide, or The Pittsburgh Courier. Hubbard’s first mention in the national press came in 1922, when he was commended for jumping 24 feet at the college level.

Indeed, Hubbard received a scholarship to attend college, which was quite rare at the time. First there was a proposal from a patron to send him to Harvard; this was politely ignored, as Hubbard was obsessed with “making it on his own,” he confessed decades later.

Then came the opportunity of a subscription contest launched by the Cincinnati Enquirer in 1921. Prompted by entrepreneur Lon Barringer, who mobilized his vast network of friends and acquaintances – including Branch Rickey, then general manager of the St. Louis Cardinals, and his good friend Fielding Yost, coach of the Michigan Wolverines – Hubbard committed to the University of Michigan in 1921. His inclusion on a Big Ten Conference varsity team shows the gradual move toward a doctrine of Northern racial liberalism.

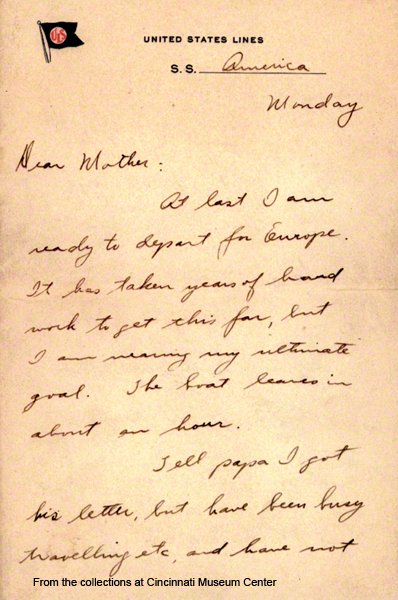

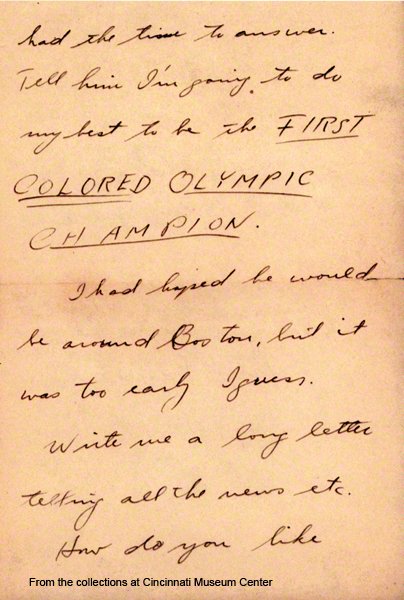

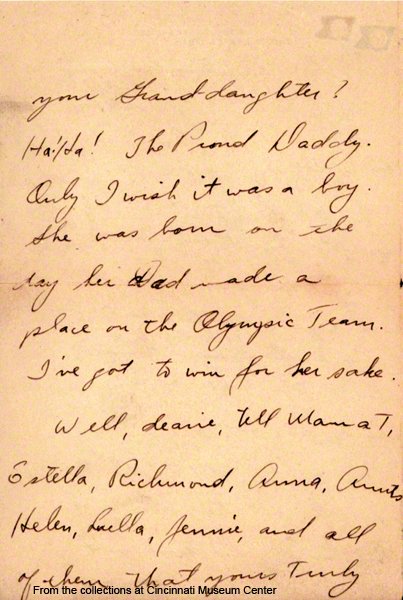

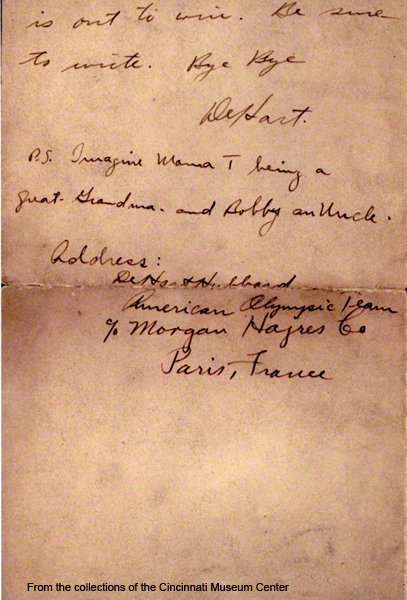

Hubbard won the A.A.U. national title in the long jump in his first year at UM, and his fame led to his selection to represent the United States at the 1924 Games. Shortly before the ship left Hoboken en route to Cherbourg, he wrote a now-famous letter to his mother promising to “do [his] best to be the FIRST COLORED OLYMPIC CHAMPION.” Only two Black athletes had won a medal so far: George Poage won two bronze medals in hurdles in 1904 and John Taylor won a gold medal in relay in 1908. Hubbard’s goal was to win the first gold medal in an individual event. He made it on his own.

It is worth remembering how normalized racial prejudice was at the time. The U.S. press in Paris explicitly gave its opinion by announcing that the American people would have preferred to be represented by Robert LeGendre in the long jump, rather than by Hubbard and Gourdin. Moreover, in spite of his excellent results, Hubbard was preceded by the White pole vaulter James Brooker for the role of captain of the U.S. Olympic team. According to Hubbard, this nomination was not exclusively a racial issue, but rather a competitive issue between fraternities, which relied on such symbolic victories to increase their influence on campus and with academic institutions. Despite this, he displayed unwavering support for the A.A.U. and continued to proudly represent the United States in France.

The Sports Diplomacy Connection

One of the fundamental principles of diplomacy is to advance the national interest. Only half a century after the U.S. Civil War, that meant rebuilding a sense of national unity. The Jim Crow laws and the Supreme Court's decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) reinforced the deep divisions and closed the door to minority groups – in particular to African-Americans. Yet, the U.S. nation was gradually structured around the industrial development of the Northeast; from Milwaukee to Philadelphia, via Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland and New York, the African-American community asserted its identity, supported by an abundant press that disseminated a substantive intellectual debate, as well as a vibrant artistic culture.

Hubbard grew up in this era of the “golden age of American sports,” during which elements such as Football Classics (Tuskegee-Morehouse, or later Howard-Lincoln), the Harlem Renaissance, or the debates between major intellectuals (W.E.B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, and Marcus Garvey), anchored these new representations of African-American culture in a context of international expansion for the United States. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the U.S. began to play a more prominent role on the world stage. In Paris, Hubbard found himself in the role of a masterful ambassador for the Black community of the Northeast United States.

Of course, the significance of the 1924 Olympic Games was not on par with what we know today. It was not yet the era of Cold War “ambassadors in short pants” or the U.S. State Department's twenty-first century Sports Envoy program. Contrary to what he had heard about the poor and nauseating U.S. delegation’s travel conditions for the 1920 Antwerp Olympiad, Hubbard had a pleasant time crossing the Atlantic, as “everyone was busy keeping in condition, and we were like a happy family,” he told The Afro-American.

Chaperoned by Earl Johnson, who took upon himself to look after the Black athletes, Hubbard witnessed the deplorable state of the Franco-American friendship: the crowd of spectators proved to be extremely partisan and particularly hostile to the Americans – not surprising, given the violence that followed the defeat of the French national team by the United States in rugby union at the Stade de Colombes a few months earlier. Nevertheless, Hubbard remained indifferent to the resentment of the French: “no wonder they were always at war if they got carried away so easily”, he thought as he reflected on his experience in Paris. In a way, the Olympic games made him a true American: he became both a respectable hero to the Black community, as well as a patriot for whom it was “heartbreaking to hear the French band play 'The Star-Spangled Banner' after America had won an event.”

Did Hubbard become an American in Paris? Not according to the standards of such like Josephine Baker. Nevertheless, his journey from “Cincy” to Paris certainly produced a mirror effect for White Americans and the Black community across the United States. “I never realized that our national anthem could be the way they made it sound,” he concluded after the disappointing display of anti-Americanism, a despondent version of the anthem one would never hear back home. While the celebration of arts and sports culture in Paris was an important step toward the making of the Black community in the United States, Hubbard, as an official representative of the U.S. sporting community in an event of international stature, contributed to the advent of American global leadership.

Mapping the Connection

From Cincinnati, Ohio to Paris, France

Further Reading

[E] Blower, Brooke L. Becoming Americans in Paris: Transatlantic Politics and Culture between the World Wars. New York, Oxford University Press, 2011, 368

[E] Mark Dyreson, “Globalizing the Nation-Making Process: Modern Sport in World History,” The International Journal of the History of Sport, 20:1, 2003, 91-106.

[F] Martin-Breteau, Nicolas. Corps politiques. Le sport dans les luttes des Noirs américains pour la justice depuis la fin du XIXe siècle. Paris, EHESS, 2020, 300.

How to Cite This Entry

Doppler-Speranza, François. “Voices: DeHart Hubbard,” FranceAndUS, https://www.franceussports.com/voices/012-dehart-hubbard. (date of consultation).