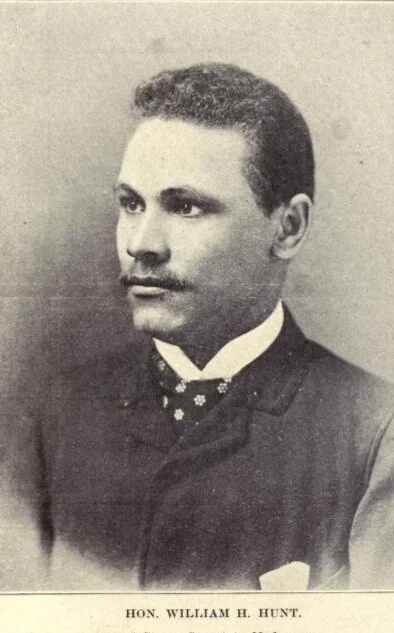

🏉🎩0️⃣0️⃣2️⃣ William H. Hunt

William H. Hunt in 1911. Source: William H. Hunt, Official Personnel Folders-Department of State (NAID 3752654); Record Group 146: Records of the U.S. Civil Service Commission; National Archives, St. Louis, MO

Meet William H. Hunt, a rugby-loving U.S. Consul and pioneer who helped grow the game in St. Étienne.

Born in 1864, Hunt attended Lawrence Academy (Groton, Massachusetts) and spent one year at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, before making his way into the business world. Following a brief tenure as clerk at the U.S. Consulate Tamatave (Madagascar) in 1898, he entered the U.S. Consular Service the following year and succeeded his future father-in-law Mifflin W. Gibbs as U.S. Consul at Tamatave in 1901. Hunt was appointed as consul at St. Étienne five years later, making him one of the rare Black Americans to represent the United States in Europe at the time. For the next twenty years, he became a mainstay of the Stéphanois community thanks in part to his role with the local rugby club.

The Context

Sports at the time were a good way for newcomers to become part of communities (just as they are today), and Hunt deployed this tool with aplomb. According to his biographer Adele Alexander, Hunt styled himself as an athletic sportsman and equestrian, a byproduct of the “muscular Christianity” concept that prized sports as a means to develop character and leadership.

Rugby at the time was esteemed by opinion-makers and the elites, thought of as a gentleman’s game yet a “modern” one thanks to its roots in England. Thus Hunt became involved with Racing Club Forézien shortly after settling in St. Étienne, and rose to serve as president--an office he retained after the club fused with another local side, Stade Forézien, in 1915. This club was later renamed Stade Forézien Universitaire (SFU) and served as predecessor to today’s Club Athletique de St. Étienne (CASE).

According to a local newspaper, Hunt was “unsackable” as president [1]. He was someone who helped grow the club, fraternized with fans, and helped forge a sense of community. “By his undeniable authority, by his kindness, by his devotion, [he] took his club to the state of brilliant prosperity,” the account proclaimed [1].

Hunt used sports in other ways during his time in St. Étienne. During the First World War (1914-1918), he organized sporting events to fundraise for local families whose breadwinners were off fighting or were killed in service of France. He did his best to track down information about loved ones captured, sick, or missing in action as a result of the war. It was personal for the President of Stade Forézien: 32 of his rugby players never returned home from the trenches, thus he fashioned the club into a community of support to help each other grieve and heal [2].

Hunt was reassigned to serve in Guadeloupe in 1927. Shortly before his departure, one Stéphanois journalist wrote that the consul would be missed not just by the Stade Forézien community, but by those across the region passionate about rugby. “The oval ball is in its rightful place in St. Étienne. This will be the glory of Mr. Hunt having fought for so long with such dedication and selflessness.”[3]

Hunt during his service as U.S. Consul in Madagascar. From Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, “Shadow and Light: An Autobiography with Reminiscences of the Last and Present Century,” 1902.

The Sports Diplomacy Connection

Hunt’s decades-long work to grow rugby in St. Étienne is an example of what today is recognized as informal sports diplomacy: the cultural, technical, and knowledge exchanges fostered through people-to-people interactions. Although Hunt was an official representative of the United States, his rugby work was separate from his government service (there was no official U.S. Government policy on sports diplomacy at the time, let alone any policies about public diplomacy). Yet, through his personal interactions on and around the rugby pitch, Hunt naturally helped to impart U.S. cultural attitudes while working to further the game.

Further Reading

(E) Adele Alexander, Parallel Worlds: The Remarkable Gibbs-Hunts and the Enduring (In)significance of Melanin, University of Virginia Press, 2010.

(E) Lindsay Sarah Krasnoff, “The Rugby-Loving U.S. Consul at St. Étienne,” Huffington Post, February 27, 2015.

(E) David Langbart, “William H. Hunt: American Pioneer,” U.S. National Archives Rediscovering Black History Blog, January 13, 2015.

[1] “Les Adieux des sportifs à M. Hunt,” unmarked, undated clipping. Folder 88 Clippings—Mention of His Name, Box 5 Magazines and Clippings, William Henry Hunt Papers (Collection 55), Mooreland-Springarn Research Collection, Howard University, Washington, DC.

[2] “Une plaque souvenir dédié aux Rugbymens morts au Champ d’Honneur a été inaugurée dimanche,” unmarked, undated newspaper clipping. Folder 88 Clippings—Mention of His Name, Box 5 Magazines and Clippings, William Henry Hunt Papers (Collection 55), Mooreland-Springarn Research Collection, Howard University, Washington, DC.

[3] “Les Adieux du SFU à leur vénéré Président Monsieur Hunt,” unmarked newspaper clipping, undated. Folder 88 Clippings—Mention of His Name, Box 5 Magazines and Clippings, William Henry Hunt Papers (Collection 55), Mooreland-Springarn Research Collection, Howard University, Washington, DC.

Mapping the Connections

From Williamstown, Massachusetts to St. Étienne, France