View from France: Baseball, A Contrary History – Part 2

This brief history of baseball in France and how the French view–or rather, how some French view(ed) the national American pastime as reflected in the French media, the only reliable record across all 130 years of this history–is in three parts. Part Two details its Interwar and immediate post-1945 eras.

Contributed by Gaétan Alibert

Babe Ruth in Paris, 1935

This brief history of baseball in France and how the French view–or rather, how some French view(ed) the national American pastime as reflected in the French media, the only reliable record across all 130 years of this history–is in three parts. Part One provides the origin story for how baseball traversed the Atlantic and its early roots in the héxagone. Part Two details its Interwar and immediate post-1945 eras, while Part Three illustrates how the game transformed in the 1980s and is currently perceived, received, and played.

Baseball wasn’t far from the limelight in the 1920s, which were a new era of growth for the National American Pastime in France, particularly in the Parisian region. A Paris league was created in 1921 and, in 1924, the French Federation of Baseball and Theca (FFBT) oversaw the early November return of the Giants and White Sox. This time, the U.S. teams played two games in Colombes in front of several thousand people, notably members of the American community whose numbers were strong in the Parisian metropolitan region. Moreover, legendary Giants manager John McGraw and the celebrated owner of the White Sox Charles Comiskey were honorary vice presidents at the behest of the FFBT.

The FFBT was created by Frantz Reichel, an eminent multi-sport athlete and director. Fiercely opposed to professional sport, he integrated several federations to guarantee amateur play and, in some cases, created federations to ensure that sport would not become professional, as in the case of baseball. Reichel wasn’t alone in this effort to protect sporting amateurism. Many clubs were founding members, notably Paris Université Club (PUC), a big omnisports club that began its baseball activities in 1923. PUC is the only surviving baseball club from this era, which thus makes it the oldest club of the French Federation of Baseball Softball (FFBS).

Although baseball remained embryonic and essentially a Parisian endeavor, the federation’s creation was an important milestone in the sport’s development. In 1926, the first baseball championship of France was launched and the French national team played its first official match in 1929. The league’s results were covered by the press, which noted that institutions like the Police prefecture, Parisian public transportation networks, and the PTT (Post, Telegram, and Telephone Office) had teams in the league, a sign that baseball increasingly expanded beyond the lonely confines of American expatriates. AS Transports took home the first French championship title in a victory against Ranelagh BC. Baseball’s increased media coverage in France enabled journalists to more regularly transport readers across the Atlantic and relay news of American baseball, particularly a player named Babe Ruth.

Babe Ruth’s notoriety was inscribed in several articles, and his salary was often much discussed. He even gave an interview to L’Intransigeant, published January 18, 1935, when he was in Paris, a fascinating exchange in which the legend responded to the question, “Do you think baseball can take over in Europe?”

“Yes, why not?” Ruth said. “In France, you would have what’s needed. For example, while walking on your boulevards, I saw well-balanced guys. You would just need to have good coaches, and baseball would need to be started very young, at six or seven years old.”

Major league salaries constantly surprised French journalists in the first half of the twentieth century. So, too, did the profits from gate receipts, as Le Figaro reported on October 17, 1923 in its announcement of the New York Yankees' first championship title. “The six matches made a total of more than three million francs!”

Baseball’s 1920s dynamic continued into the 1930s. It remained a closeted sport, but it existed and made the talk of the town from time to time. The prestigious journal L’Auto even sponsored an international tourney between France, Belgium, and the Netherlands in June 1937 at Pershing Stadium in Paris; coverage of the competition noted,

“The French know little about this game, which is the national game of the Americans. Their technique is a bit disconcerting if you compare it to the sports practiced in Europe.”

Once again, the exotic aspect of the game strongly marked baseball. Although it remained a niche practice, another article in L’Auto from March 30, 1937, attempted to give the game another chance in the aftermath of a rugby match. The piece, “Le base-ball. On demande à revoir,” reluctantly noted the absence of pedagogy around baseball’s rules in order to make it more intelligible to a public that was curious, but ignorant, of the game. However, the reporter complimented the game,

“Yesterday, in any case, we realized the attractions and the spectacular side of this exercise. That’s already a huge point…In general, moreover, baseball appeared as a sport requiring extremely advanced training. It is obvious, for example, that passes made at full speed, at long distances and whose precision must be perfect, cannot be successful by ordinary mortals.”

The reporter concluded that, “in a word, baseball appeared as a very complete, spectacular game, for which one understands that the masses can be passionate.”

Yet, baseball never became a mass sport. It was believed to have disappeared for a time during the Second World War. We now know that the French Baseball Federation continued its activities in the métropoloe and Tunisia, where baseball was introduced by an American, Dr. Kelly, before the war. It was also in Tunisia immediately post-war that French baseball became most developed and shined. Local newspapers chronicled weekly results of the senior and junior leagues, as well as activities of the Tunisian league–even its internal problems. The best players were featured, many of who were on the French national team. After Tunisia gained independence in 1956, many of its biggest baseball names went to France, joined clubs like PUC, or created their own teams, notably in the south of France. Baseball was also present in Morocco and Algeria during this period, although it was less developed than in Tunisia.

On the mainland, American soldiers added to French baseball. Just as they did in the 1917 to 1919 era, the Americans practiced baseball on a grand scale through military championships as several Major League Baseball players (Sam Nahem, Ewell Blackwell, Dave Koslo, Merv Connors, Harry Walker, Murry Dickson) or those from the Negro Leagues (Leon Day, Monte Irvin, Willard Brown) were stationed in-country. Certain U.S. bases were akin to immense cities and had numerous baseball and softball pitches. Some soldiers even had the mission to introduce the French to baseball, such as Major Leaguer Zeke Bonura in 1944 in Marseille. It was not uncommon for matches to be advertised in the French press or to the local population.

French media, both the written press as well as film documentaries, continued to treat baseball as the supreme cultural reference of America and a maker of unusual stories in the mid-to-late 1940s. Thus, the communist daily L’Humanité mentioned in its January 3, 1950 edition that the Saint Louis Cards hired a psychologist to help the team win. Libération on April 21, 1949, joked that the 29 members of the Ohio House of Representatives who individually sent a telegram to the Vice-President of the State to announce the death of their grandmother in order to justify their absence from the Congressional session, really used the fake family death to hide attendance at a Cincinnati Reds game. There was a full page devoted to the All-American Girls Professional League, the famous women's baseball league, in the March 1947 edition of V magazine, the journal of the National Liberation Movement, a former resistance organization. Like V or Libération, Franc-Tireur was a press organ from the Resistance. And like several French media, it devoted an article, including a photo, to Babe Ruth’s death in August 1948, confirming the status of the Bambino’s sporting legend in France.

An article from the daily newspaper L'Équipe on March 8, 1950, scratched the question about baseball when it asked,

“Why is baseball the number one sport (in terms of popularity) despite two handicaps: short season and being a virtually non-existent spectacle?”

Voilà, a point of view already raised on French opinion of baseball but which remained rare in the available sources. At the time of publication, as previously noted, baseball was often described as exactly the contrary: spectacular. The point of view of this article was perhaps shared by the majority of French people because, from the 1950s to the 1970s, French baseball remained embryonic, despite the presence of American bases until 1966, when the French withdrawal from NATO general command and General De Gaulle’s demands closed U.S. bases throughout the country. And with it, the baseball played on such military bases, including children’s Little League teams, one of which even qualified for the final tournament in the United States in 1962. Nonetheless, there wasn’t a strong link between this baseball and that practiced by French clubs.

Paris Université Club, 1969

A 1971 French television report presented by sports journalist Michel Drucker noted that France had 10 baseball clubs for 250 practitioners. He spoke of it as a “slightly mysterious sport” for the French. The report’s voice-over described baseball as a series of “mysterious rites” that can be understood after “a long initiation.” Drucker explained the rules then discussed baseball in the United States, with an initial focus on the professional game’s lucrative financials and a reference to a fascination for the wealth generated by this sport. A year earlier, an article of the famous daily Le Monde reported on 13 clubs. In this article of April 27, 1970, the journalist asked the question, “is it not sacrilege to play the American national sport in France?” The captain of PUC, future president of the FFBS Olivier Dubaut, answered, “This is exactly the kind of prejudice that harms us and that we want to fight.”

Original En Français

D’ailleurs, la lumière pour le baseball français n’est pas loin. En effet, les années 1920 vont voir une nouvelle poussée de croissance du sport national américain en France, particulièrement dans la région parisienne. Un championnat de Paris est créé en 1921 puis, en 1924, la Fédération Française de Baseball et de Thèque (FFBT) voit le jour en marge du retour en France, début novembre, des Giants et des White Sox. Cette fois-ci, les deux équipes peuvent jouer à Colombes deux rencontres de baseball qui vont ramener plusieurs milliers de personnes, essentiellement des membres de la communauté américaine, fort nombreuse à Paris et sa région. D’ailleurs, le manager des Giants, le légendaire John McGraw, et le célèbre propriétaire des White Sox, Charles Comiskey, seront les vice-présidents d’honneur à la création de la FFBT. Cette dernière est créée par Frantz Reichel, éminent membre du sport français, athlète multi-sport et grand dirigeant sportif. Farouchement opposé au sport professionnel, il va intégrer plusieurs fédérations pour y garantir l’amateurisme et, dans certains cas, créer des fédérations pour éviter que le sport ne devienne professionnel, comme dans le cas de la fédération de baseball. Reichel n’est pas seul à la création. Plusieurs clubs sont membres fondateurs, notamment le Paris Université Club, grand club omnisports parisien qui a débuté ses activités baseball en 1923 et qui reste le seul club survivant de cette époque, ce qui en fait le club doyen de la FFBS (Fédération Française de Baseball Softball).

Même si le baseball reste embryonnaire et essentiellement parisien, la création de la fédération permet de passer un cap en matière de développement. 1926 voit ainsi la création du premier championnat de France et 1929 le premier match officiel de l’équipe de France. Les résultats des championnats sont donnés par la presse, ce qui permet de savoir que des institutions telles que la Préfecture de Police, les transports parisiens ou les PTT (Poste, Télégramme et Téléphone) avaient des équipes au sein du championnat, signe que le baseball sort de plus en plus du seul giron des expatriés américains. C’est d’ailleurs l’AS Transports qui remporte le premier titre de champion de France face au Ranelagh BC. En plus de nous parler du baseball en France, la presse de l’époque peut régulièrement franchir l’Atlantique pour évoquer l’actualité du baseball américain, particulièrement un homme, Babe Ruth. La notoriété du Babe est telle que plusieurs articles lui seront consacrés, notamment pour évoquer son salaire. Il aura même droit à une interview dans le journal L’Intransigeant du 18 janvier 1935 quand il sera de passage à Paris. Un intéressant entretien où il répond à la question « Pensez-vous que le baseball puisse prendre en Europe ? »

« Oui, pourquoi pas ? En France, par exemple, vous auriez des éléments. En me promenant sur vos boulevards, j’ai vu des gars bien balancés. Seulement, il faudrait que vous ayez de bons entraîneurs et le baseball doit être commencé très jeune, à six ou sept ans ».

D’une manière générale, les salaires dans les Ligues Majeures vont étonner plus d’une fois les journalistes français dans la première moitié du XXème siècle, ou bien les recettes de matchs, comme dans l’article que Le Figaro publie le 17 octobre 1923 pour annoncer le premier titre de champion des New York Yankees « Les six matches firent au total une recette qui dépasse trois millions de francs ! ».

La dynamique des années 1920 se poursuit la décennie suivante. Le baseball reste un sport confidentiel mais il existe, faisant même parler de lui de temps en temps. Le prestigieux journal L’Auto va même parrainer un tournoi international à trois, entre la France, la Belgique et les Pays-Bas, en juin 1937 au stade Pershing de Paris, écrivant dans l’article de présentation de la compétition « Les Français connaissent peu ce jeu qui est le jeu national des Américains. Sa technique déconcerte un peu si on la compare aux sports pratiqués en Europe ». Une nouvelle fois, l’aspect exotique du jeu est un marqueur fort du baseball, ce qui en fait encore une pratique insolite au sein du sport français, même si un autre article de L’Auto, datant du 30 mars de la même année, semble vouloir lui donner une chance après un match d’exhibition suivant un match de rugby. L’article titré « Le base-ball . On demande à revoir » regrette le peu de pédagogie autour des règles pour rendre le jeu intelligible à un public curieux mais ignorant du baseball. Mais il se montre aussi élogieux sur le jeu lui-même « Hier, en tout cas, on se rendit compte des attraits et du côté spectaculaire de cet exercice. C’est déjà un point énorme ». Plus loin « D’une façon générale d’ailleurs, le baseball apparut comme un sport exigeant un entraînement extrêmement poussé. Il est évident, par exemple, que les passes effectuées à toute volée, à des longues distances et dont la précision doit être parfaite, ne peuvent être réussies par le commun des mortels ». Et il conclut « En un mot, le base-ball apparut comme un jeu très complet, spectaculaire, et pour lequel on comprend que les masses puissent se passionner ».

Le baseball ne devînt pas un sport de masses. On crût même, pendant longtemps, qu’il avait disparu durant la Seconde Guerre Mondiale. On sait maintenant que la Fédération Française de Baseball continua ses activités, tant en métropole qu’en Tunisie, où le baseball fut introduit par un américain, le docteur Kelly avant la guerre. C’est d’ailleurs en Tunisie, après-guerre, que le baseball français fut le plus développé et rayonnant. Les journaux locaux rendaient compte chaque semaine des résultats des championnats seniors ou jeunes ainsi que des activités de la ligue tunisienne, et même de ses problèmes internes. On y trouvait également les meilleurs joueurs et nombre d’entre-eux constituèrent l’équipe de France. Après que la Tunisie obtînt son indépendance en 1956, plusieurs grands noms du baseball tunisien vinrent en France, rejoignant des clubs comme le Paris Université Club ou créant leurs propres clubs, notamment dans le sud de la France. Le baseball fut également présent au Maroc et en Algérie durant cette période même s’il fut moins développé qu’en Tunisie.

En métropole, s’ajouta au baseball français, celui des soldats américains. Comme entre 1917 et 1919, les Américains pratiquèrent le baseball à grande échelle, au sein de championnats militaires où évoluèrent plusieurs joueurs de la MLB (Sam Nahem, Ewell Blackwell, Dave Koslo, Merv Connors, Harry Walker, Murry Dickson) ou des Negro Leagues (Leon Day, Monte Irvin, Willard Brown). Certaines bases américains étaient pareilles à d’immenses villes, disposant de nombreux terrains de baseball et de softball. Certains soldats eurent même comme mission d’initier les français au baseball comme le Major Leaguer Zeke Bonura en 1944 à Marseille. Il n’était pas rare que les matchs soient annoncés dans la presse française ou auprès de la population locale. Plus généralement, durant les deux dernières années de la guerre et dans l’immédiate après-guerre, les médias français, presse écrite ou documentaires filmés, continuèrent de traiter du baseball comme référence culturelle suprême de l’Amérique et faiseur d’histoires insolites. Ainsi, le quotidien communiste L’Humanité évoque, dans son édition du 3 janvier 1950, que les Cards de Saint Louis ont embauché un psychologue pour aider l’équipe à gagner. Ou encore cet article du journal Libération, en date du 21 avril 1949, s’amusant que les 29 membres de la chambre des représentants de l’Ohio, envoyèrent chacun un télégramme au vice-président de l’État pour annoncer la mort de leur grand-mère afin de justifier leur absence à la séance du Congrès, le faux décès familial cachant en réalité un match des Reds de Cincinnati. On pourrait ajouter la pleine page consacrée à la All-American Girls Professional League, la célèbre ligue féminine de baseball, dans l’édition de mars 1947 du magazine V, revue du Mouvement de Libération Nationale, ancienne organisation résistante. Comme V ou Libération, Franc-Tireur était un organe de presse issu de la Résistance. Et comme plusieurs médias français, il consacra un article, avec photo, à la mort de Babe Ruth en août 1948, confirmant le statut de légende sportive du Bambino, jusqu’en France.

Un article du quotidien L’Équipe, du 8 mars 1950, égratigne, quant à lui, le baseball « Pourquoi le base-ball est-il le sport numéro un (sur le plan de la popularité) malgré deux handicaps : saison courte, spectacle pratiquement inexistant ? ».

Voilà un point de vue déjà lu mais qui reste rare dans les sources disponibles sur l’avis que l’on se fait en France du baseball depuis son apparition, puisque à la publication de cet article, on l’a vu, le baseball a souvent été décrit comme, au contraire, spectaculaire. Le point de vue de cet article est peut-être partagé par la majorité des Français car, des années 1950 aux années 1970, le baseball français reste embryonnaire, malgré la présence de bases américaines jusqu’en 1966 et le retrait de la France du commandement de l’OTAN, le général De Gaulle exigeant la fermeture de bases US sur l’ensemble du territoire. Bases où on jouait au baseball, notamment les enfants au sein d’équipes de Little League, l’une d’elles se qualifiant même pour le tournoi final aux États-Unis en 1962. Il semble qu’il n’est pas existé de liens solides entre ce baseball et celui pratiqué par les clubs français.

Un reportage de la télévision française de 1971, présenté par Michel Drucker, alors journaliste sportif, indique que la France compte 10 clubs pour 250 pratiquants. Michel Drucker parle d’un « sport un peu mystérieux » pour les Français. La voix-off du reportage parle, elle, du baseball comme fait de « rites mystérieux » que l’on peut comprendre après « une longue initiation ». Après avoir expliqué les règles, le journaliste évoque le baseball outre-Atlantique parlant en premier lieu de l’argent qui entoure le baseball, renvoyant là encore à une fascination pour les richesses que génère ce sport aux États-Unis Un an avant, un article du fameux quotidien Le Monde, parle de 13 clubs. Dans cet article du 27 avril 1970, le journaliste se pose la question s’il n’est pas sacrilège de jouer en France au sport national américain, ce à quoi le capitaine du PUC, futur président de la FFBS, Olivier Dubaut, répond « Voilà exactement le genre de préjugés qui nous fait du tort et que nous voulons combattre ».

This article would not be as complete without the historical work of Jean-Cristophe Tiné, former Secretary-General of the Fédération Française du Base-Ball et Soft-Ball, and author of the blog Une Histoire Oubliée d’un Sport Méconnu, a significant memorial to the first decades of baseball in France http://thenextbaseballcountrywillbefrance.blogspot.com/

Gaétan Alibert is a writer on baseball and sports culture, author of Une histoire populaire du baseball (blacklephant editions), host of the Culture Baseball podcast, and contributor to HYPE Sports, The Strike Out and Ecrire Le Sport. He is also a member of Federal Memory commission of French Baseball Softball Federation. Follow him on Twitter @GaetanAlibert.

American Football in France

Often hidden from sight, American football has long served as a conduit between French and Americans on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

Contributed By Dr. Russ Crawford

Often hidden from sight, American football has long served as a conduit between French and Americans on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. For the first several decades, however, it was a game played in France by Americans. The sport was first exhibited in 1900 Paris and scrimmages held between the crews of visiting U.S. warships in French ports, but the Great War changed this.

The InterAllied Games in 1919. Image from Le Football: A History of American Football in France (used with permission by the National World War I Museum in Kansas City, MO via Russ Crawford).

The first American football games in France were played by soldiers of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in World War I. During the war, doughboys played for rest and relaxation, and to keep themselves safe from supposed temptations like....women, wine, and gambling. Similarly, after the war, AEF soldiers waiting to be demobilized played football to keep busy. These games included a division-level tournament that culminated in a championship game played at Stade Pershing in Paris as part of the Inter-Allied Games in 1919. Back in the United States, the war helped popularize football but it did not receive the same boost in France.

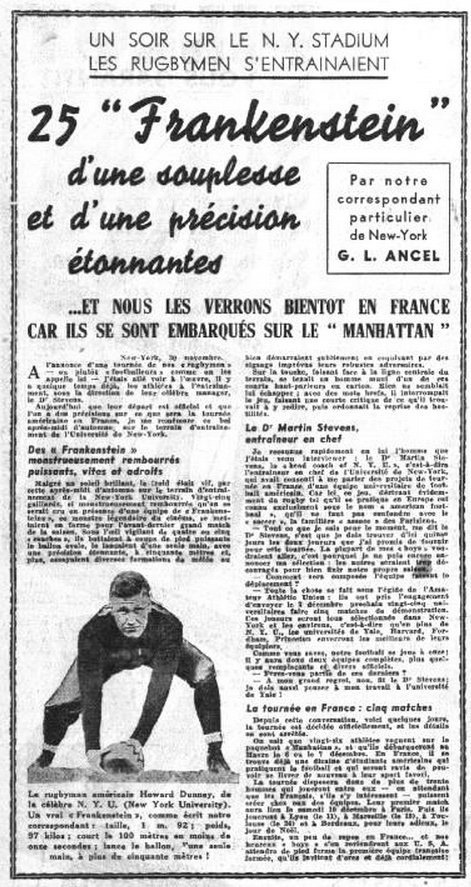

This changed in 1938, with concerns over renewed war building in France. Kurt Riess, a German writer working as a reporter for the French newspaper Paris Soir, had the idea that what France needed was American football. He convinced his paper to organize an exhibition tour by two all-star teams led by Fordham University head coach Jim Crowley. The two teams played six games and garnered significant press attention, at least in the buildup stage, and for the first game played in Paris.

From Le Petit Parisien, December 1, 1938. Image from Le Football: A History of American Football in France (used with permission of the Bibliothéque Nationale de France via Russ Crawford).

When the United States joined the Second World War, American servicemen continued the games in French territory, beginning with the Arab Bowl in Oran Algeria in 1944. Various teams played in “Bowl” games in Paris, Dijon, Cherbourg, and Marseilles. A scheduled Champagne Bowl was cancelled by the Nazi’s final Ardennes Offensive.

France also played an indirect role making football a better spectacle in the United States during WWII. According to Clark Shaughnessy, then coach of the Stanford Indians, the German blitzkrieg that rolled through France in 1940 inspired him to revamp his offense into what would be popularized as the T Formation. That formation featured a great deal of misdirection and trickery to confuse the defense, as had the German invasion faking the Allied armies north into Belgium before striking through the Ardennes.

Between 1952 and 1966, the Fourth and Fifth Republics, as part of NATO, allowed the United States to build military bases on French soil. By the late 1950s, teams from France began to dominate the U.S. Air Force Europe (USAFE) league. Despite the hundreds of games played on their soil, very few French citizens ever saw a football contest.

In addition to games played by USAFE teams, American high schools attached to the various French bases also played football to give their students the same prep experience as their peers back home. Some of these prep teams also played internationally, facing teams from Germany, England, and Spain.

A 1961 tour of southern France by the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) Indians and the Laon Rangers included games in Toulouse and Perpignan. The tour was conceived by Marcel LeClerc, who directed the Marseilles rugby club, and who paid all of the expenses for the tour. He wanted to popularize the American sport in the south where rugby was most popular, but the effort was unsuccessful.

In 1976, Bob Kap, an entrepreneur originally from Yugoslavia, who argued soccer-style kickers were better for the NFL, began his quest to popularize football in Europe. His International Football League sponsored a tour of Europe by the Texas A&I Javelinas and the Henderson State Reddies, two top National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) football teams. They played one game of their series in Paris and once again garnered significant press, but only for a few days.

In 1977, Kapp convinced the semiprofessional Newton (IA) Nite Hawks and the Chicago Lions to play several games in Europe, including one in Paris and another in Lille. Though they drew decent crowds, and received some favorable press while in France, by the time the tour reached Austria things fell apart and team officials had to get a check cashed by the U.S. Embassy to pay for their hotel so they could leave for home.

Into the 1980s, others attempted to bolster the sport’s popularity in Europe via the portal of France. Jim Foster, who created the Arena Football League, took the Detroit Drive and the Chicago Bruisers to Europe after the 1989 season, where the teams played exhibitions in London and Paris. Although the games netted a number of spectators, Foster credited the games in Europe with helping spread the popularity of his new league.

The NFL also attempted to bring football to the continent with NFL Europe between 1991 and 2007, but they were unable to convince the French to take part. Several French players saw action, but the effort ultimately failed to establish big-time professional American football anywhere in Europe.

Laurent Plegelatte (left) throwing a pass against Les Anges Bleus in the 1986 Casque d'Or FFFA championship game. Image from Le Football: A History of American Football in France (via Russ Crawford).

The tables turned in 1980, however, when American football played by the French took firmer root. That year Laurent Plegelatte, a French physical education instructor in the greater Paris region, traveled to Colorado for a conference; while there, he watched practices and games at a local high school. According to Plegelatte, when a coach ridiculed the idea that Frenchmen could play football, he decided to prove the critic wrong. He then approached the owner of a sporting goods store and bought enough equipment to start a team. Within a few hours of his return to Paris, he held a practice and had formed the first all-French team – the Spartacus. Fittingly, they practiced on the grounds of Stade Pershing.

Plegelatte proved to be a visionary. He required that his players learn the sport while playing for Spartacus, and then leave to form their own squad. In this manner, within a few years there were several teams playing in and around the Paris area.

Spartacus, the Meteores, and the Anges Bleus (Blue Angels), along with others, pioneered the sport around Paris. The Blue Angels, in particular, began to elevate the level of play by bringing in American players, and Canadian coach Jacques Dussault to help improve the level of play in the league. Other teams, such as the Flash de La Courneuve, used the sport to build community in the economically blighted area where they played, and forged strong programs that continue today. Despite facing the stigma of sometimes being called “Reagan Americans,” the players became fanatics in their devotion to the unusual sport.

Canal +, the French television network, began to televise American football games in the early 1980s, which accelerated team creation, and spread the game from the capital. The Argonautes of Aix-en-Provence was a power in the 1990s. The Spartiates of Amiens, and the Black Panthers of Thonon-les-Bains had championship runs in the 2000s.

The Sparkles de Villeneuve St. Georges taken before their first game against the Spanish National Team. Image from Le Football: A History of American Football in France (photo courtesy of Rémy Issaly vis Russ Crawford).

In 2011, when Sarah Charbonneau created the Sparkles de Villaneuve St. George, women began to play as well. The Molosses d’Asniere-sur Seine, a successor team to the Sparkles, has won all of the Challenge Femin that the FFFA has held. Support from the FFFA has reportedly been grudging, and the Federation recently elevated flag football, instead of tackle, for women.

The most accomplished French player so far has been Richard Tardits, who remains the second leading sack producer in Georgia Bulldog football history. Tardits, who went out for the Bulldogs on a whim, also played professionally in the NFL for the Phoenix Cardinals and New England Patriots from 1989 to 1992 before an injury cut short his career. Jacques Accambray, a former FFFA president, played football and threw the hammer for the track team while attending Kent State University in the early 1970s. In recent years, more and more French players have found places on college teams in the United States and Canada. Purdue wide receiver Anthony Mahoungou played briefly for the Philadelphia Eagles, and most recently Jeffery M’ba signed to play with Auburn University.

Today, more than 23,000 Frenchmen, and dozens of Frenchwomen, play the game on more than 225 teams. The FFFA also sponsors junior teams, flag teams, and cheerleading competitions.

Dr. Russ Crawford is a Professor of History at Ohio Northern University who runs the Women Playing American Football Oral History Project. The University of Nebraska Press published Crawford’s Le Football: A History of American Football in France in 2016.